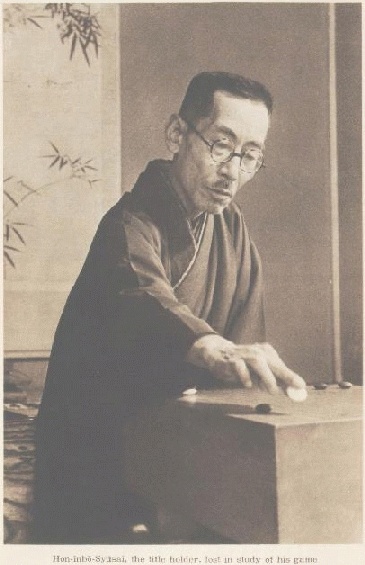

Shusai

Honinbo Shusai (本因坊秀哉 Hon’inbō; Shūsai, Tamura Hoju, Tamura Yasuhisa (田村 保寿), 1874 – 18 January 1940) was a Japanese professional go player.

| Table of contents | Table of diagrams The infamous [myoshu] |

Honinbo Shusai was the 21st and last hereditary head of the Honinbo house, and 10th and last historic Meijin. He played a role in founding the Nihon Kiin, turned the hereditary Honinbo title over to the Nihon Kiin to be used as a tournament title, and was a student of Honinbo Shuei.

Early Go career

Prior to becoming the 21st head of the Honinbo house (1908), Honinbo Shusai was known as Tamura Yasuhisa. This was the name that appeared on his kifu when he was still a pupil of Honinbo Shuei. While Shuei was alive, Tamura was the only player who was strong enough not to need any more handicap than playing Black every game. Shuei played the next strongest, Karigane Jun'ichi under the Match Handicap System of sen-ni, where the weaker player alternates between black and 2 stones.

Ascension to Meijin

After Shuei died in 1907, there was a dispute over whether Tamura or Karigane should become the next Honinbo. Karigane had some supporters including Shuei’s widow. Shugen, as the caretaker 16th Honinbo, became caretaker 20th Honinbo. In 1908, Shugen resigned the Honinbo title to Tamura as the strongest living player, who thus became the 21st Honinbo, known henceforth as Honinbo Shusai.

Dominance of Japanese Go

Shusai became the only living 8 dan in 1911. In 1914, he became Meijin and thus the only living 9 dan, by acclaim of his fellow players. He seems to have been at least a stone stronger than his nearest rivals. According to ![[ext]](images/extlink.gif) Games by Honinbo Shusai, he played 37 no-handicap games with White from 1914 to 1927 (excluding consultation games), scoring 20 wins and 17 losses. Iwamoto Kaoru used his own victory over Shusai (B+R, 1926) as an illustrative game in his book Go for Beginners, saying that Shusai was one of the strongest players of the century. Segoe Kensaku was a rare opponent who proved too strong for handicap stones and also won 3–1 playing Black.

Games by Honinbo Shusai, he played 37 no-handicap games with White from 1914 to 1927 (excluding consultation games), scoring 20 wins and 17 losses. Iwamoto Kaoru used his own victory over Shusai (B+R, 1926) as an illustrative game in his book Go for Beginners, saying that Shusai was one of the strongest players of the century. Segoe Kensaku was a rare opponent who proved too strong for handicap stones and also won 3–1 playing Black.

He beat some lower-ranked professionals on 2 or even 3 stone handicap. E.g. the leading female player Kita Fumiko usually played him on 2 stones even after she became 5 dan, with a roughly even score. One of her star pupils, Ito Tomoe, when 2 dan, scored 1–1 at 3 stones. The year Shusai became 8 dan, Shusai beat another female pro, Takeda Itsuko 2d at 3 stones. This game was used as a model for one of the Hikaru No Go/Games, Chapter 70.

Some of the future leaders in the Go world were distinguished early by being too strong for Shusai to give the required handicaps to, e.g. Takagawa Kaku, Fujisawa Kuranosuke, Go Seigen, Kitani Minoru, and Iwamoto Kaoru. Handicap Go uses some of these 3-stone victories as examples of how to play handicap Go as Black against strong opposition.

Later years

Even in his 50s, he seemed to be much stronger than anyone else. E.g. he won the Famous Killing Game Of 1926 as white against Karigane Jun'ichi. This was used as a model for Hikaru No Go/Games in Chapter 8, Hikaru Shindo vs. Tetsuo Kaga. At 60, he beat Go Seigen playing white, albeit with some controversy (see below).

Shusai’s 1938 retirement game against Kitani Minoru was the subject of Kawabata Yasunari’s famous novel The Master of Go. Shusai lost by 5 points playing white; Kitani played well enough to keep his first move advantage.

Style

Shusai was a slow and deep player. He used this time to read deeply. Shusai’s strength was fighting and reading, perhaps because all the handicap games he played even against strong players. When he played White, he would make longer and sometimes higher extensions, which were looser but covered weak spots more evenly.

But later players didn’t build on his opening styles because of the arrival of the Shin Fuseki late in Shusai’s career. Later players also preferred Shuei’s overall elegance to Shusai’s sometimes brute force approach. One aphorism was that one should ideally play Black like Shusaku, White like Shuei, and handicap play as white like Shusai.

An infamous play

Shusai played a famous game with Go Seigen in which there was a lot of controversy surrounding multiple adjournments during the game. Maeda Nobuaki is supposed to have been the one to find  in the following diagram. There was, of course, a lot of controversy surrounding this accusation. Anyway, the fact that such a winning move existed on the board means that White had outplayed Black and more than nullified the first move advantage by move 160 in this no-komi game.

in the following diagram. There was, of course, a lot of controversy surrounding this accusation. Anyway, the fact that such a winning move existed on the board means that White had outplayed Black and more than nullified the first move advantage by move 160 in this no-komi game.

Pupils

- Kogishi Soji, so brilliant that Shusai wanted him to be heir, but he died young of typhoid

- Murashima Yoshinori

- Hayashi Yutaro

- Fukuda Masayoshi

- Maeda Nobuaki

- Miyasaka Shinji

- Kanbara Shigeji

- Miyashita Shuyo

- Shikama Chiyoji

- Murata Seiko

- Takeda Hiroyoshi

- Masubuchi Tatsuko

- Karibe Eisaburo

Books

- By Shusai:

- Shikatsu Myoki (1910) — Shusai’s Life and death problem book aimed at high dans

- Shiroto Kikan Jissen Shokai (素人棋鑑) (1910) — Shusai complemented Honinbo Shuei’s original comments on amateur games

- Game collections:

- Honinbo Shusai - Complete Game Collection

- The Japanese National Diet Library has two collections of his games available:

-

![[ext]](images/extlink.gif) vol.1 of his Complete Games. 126 games covering 1887-1897, with commentaries from Igo Shinpo magazine.

vol.1 of his Complete Games. 126 games covering 1887-1897, with commentaries from Igo Shinpo magazine.

-

![[ext]](images/extlink.gif) vol.2 of his Selected Games. 68 games covering 1899-1938, with his own comments.

vol.2 of his Selected Games. 68 games covering 1899-1938, with his own comments.

-

- Individual games:

- About Shusai’s 60th birthday game (the “Game of the Century”) against Go Seigen in 1933–4

- Old Fuseki vs New Fuseki: Honinbo Shusai plays Go Seigen (John Fairbairn, 2011) — A game commentary and history book

- About Shusai’s 1938 retirement game against Kitani Minoru:

- The Master of Go (Kawabata Yasunari, 1951) — A novel based on the game

- The Meijins Retirement Game (John Fairbairn, 2010) — A game commentary and history book

- About Shusai’s 60th birthday game (the “Game of the Century”) against Go Seigen in 1933–4

See Also

-

![[ext]](images/extlink.gif) Games by Honinbo Shusai — SGF files

Games by Honinbo Shusai — SGF files

- Famous Killing Game of 1926 — Good example of Shusai’s reading skills against long-time rival Karigane Junichi

- Game of the Century — Shusai’s 60th birthday game with Go Seigen in 1933–4 (see also the section above An infamous play)

![[Diagram]](diagrams/3/1ec108e486f0810c7a3a4afee13b737c.png)

![Sensei's Library [Welcome to Sensei's Library!]](images/stone-hello.png)